Almost three decades ago, the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt marked the end of the Empire with legs of iron and feet of clay. For more than 45 years, the world was divided into two blocks. The commercial and financial exchanges between the two sides of the Berlin-wall were minimal. The dismantling of the Soviet Union juxtaposed with the beginning of the globalization in Western capitalism. Global economy entered a new era, and so did the financial crime.

Ex-Soviet states embraced capitalism, but at the time, they did not have the right policies nor the appropriate legal systems to deal with the challenges of the transition. Nevertheless, the transfer of ownership of businesses and properties from the government to privately owned entities and private individuals was engaged. Organized crime and corruption were for sure, a big issue and new authorities were not able to implement effective policies to control the new-born markets. In this context, capital ownership concentrated in the hand of several people or groups of interest, later known as oligarchs.

From the early days of the roaring 1990s, many "investors" from the developed countries searched their fortune in the ex-Soviet bloc. Hermitage Capital Management, founded in 1996 by American entrepreneurs, is such an example and got highlighted in the media during the Magnitsky case.

Trade of goods and services, as well as transfers of capital between ex-Soviet countries and the developed democracies, increased, especially in the early 2000s. The asymmetry in regulations and legal framework facilitated the proliferation of financial crime. One the on hand, shady individuals and organization were using the ex-Soviet countries to dissimulate illicit gains. On the other hand, the oligarchs, as well as figures of organized crime, used Western countries to hide or keep their assets away from justice.

The climax of this system came after the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine and the set of sanctions inflicted to companies from the Russian Federation aimed to curtail the avenues of money laundering and tax evasion. But, this system that emerged during the 1990s is so intricated with the real globalized economies from both developed and ex-Soviet countries, that sanctions or similar measures may not solve the matter.

“What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that their security did not rest upon the threat of instant U.S. retaliation to deter a Soviet attack, that we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?”

President Ronald Reagan, 1983

COVID-19: Furlough scheme fraud

Her Majesty's Customs and Revenue unfold the first wave of arrests in fraud cases related to furlough scheme. HMRC's officers indicted a suspect in West Midlands, and this is most likely only the first step from a more significant set of actions against this new type of fraud.

During the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the British government introduced a package of stimuli to help mitigate the impact of the lockdown on the real economy. One of those measures was the furlough scheme which paid pays 80 per cent of salary costs for furloughed staff. The programme encompassed both permanent and temporary workers.

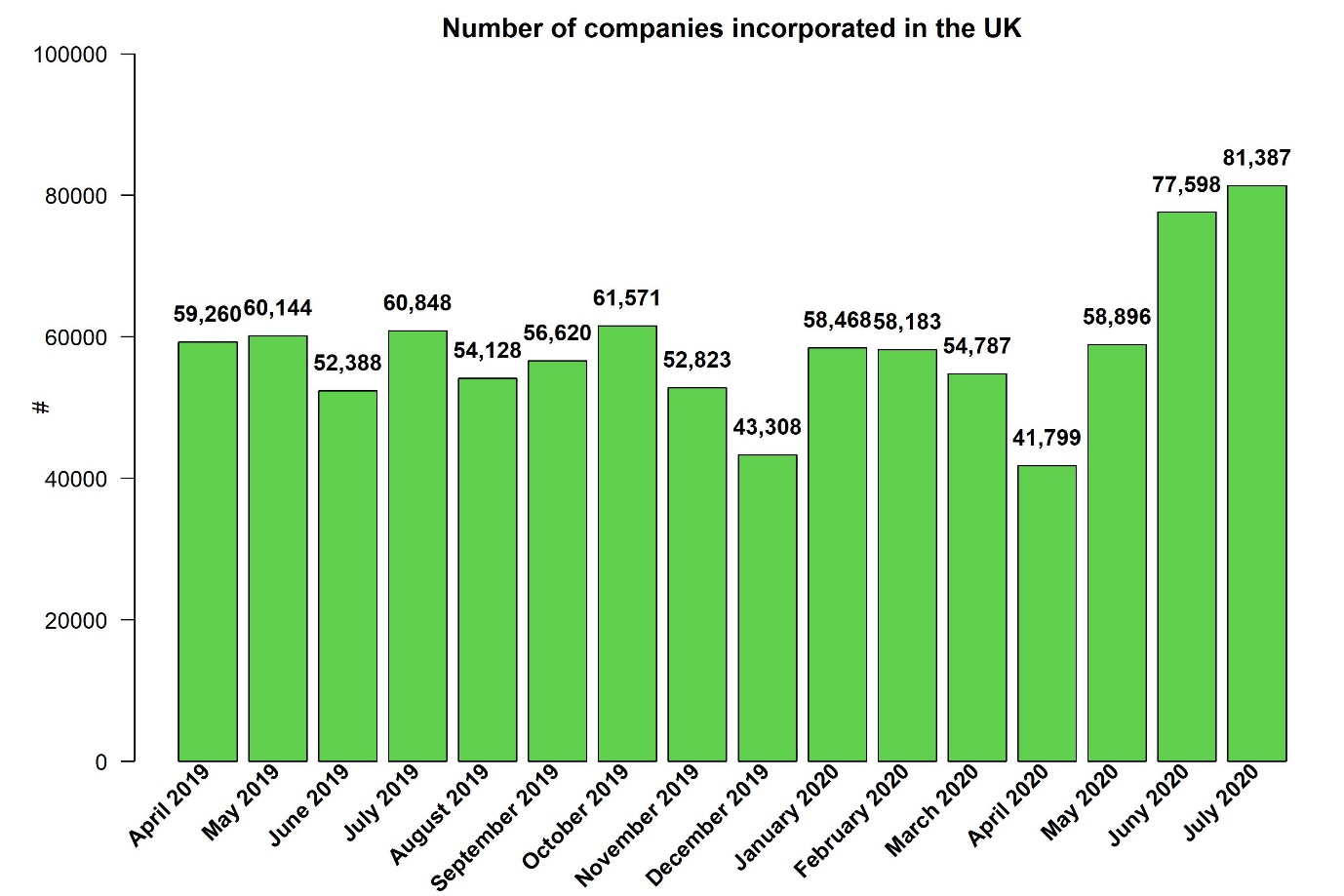

From late June, the UK tax authority signalled scams aiming to take advantage of the furlough scheme. Despite, the lockdown and the GDP contraction of over 20% observed in the second quarter, Companies House observed a significant number of newly incorporated companies in the UK. In April, more than 41 thousand new companies were registered, and over the following three months, the number increased steadily to more than 81 thousand in July. Despite the economic recession, the number of newly opened businesses between May and July 2020, was with 30% higher compared to the same period in 2019.

Needless to say, that this trend fuelled HMRC’s suspicions of a big wave of fraud, abusing the governmental help. The short-term reaction came from commercial banks that delayed the business account opening process during the pandemic. Most banks refused to open bank accounts for newly created businesses since the coronavirus outbreak. Neobanks like Monzo and Revolut saw an opportunity and onboarded some of the customers left aside by the traditional banks. Therefore, we could expect new indictments concerning the furlough scheme pointing the finger at Fintechs.

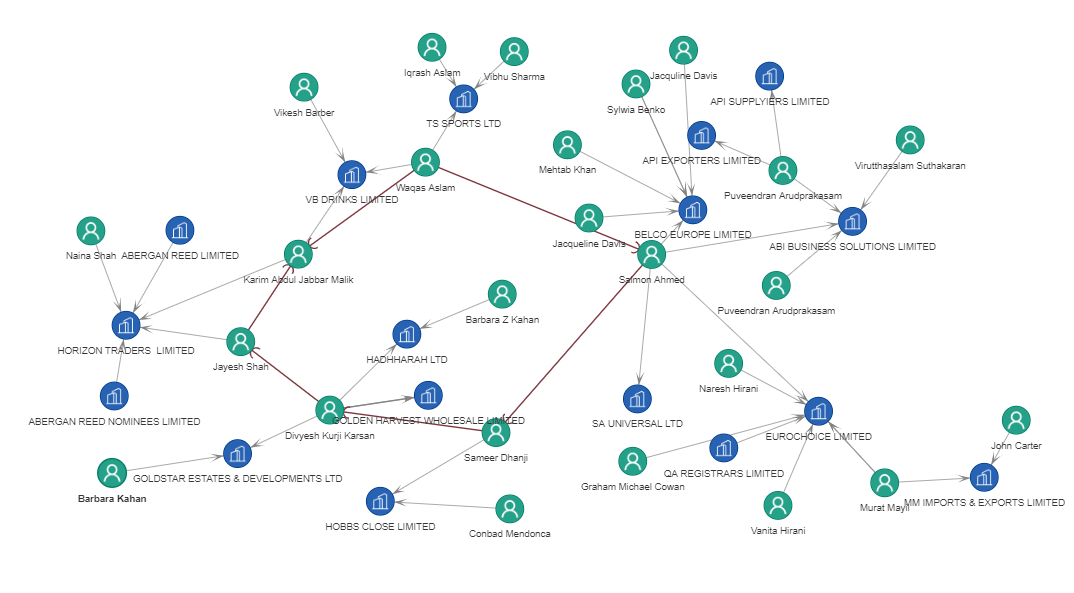

Tax Evasion: Dismantling VAT fraud

HMRC dismantled last year a major criminal operation involved in VAT fraud. The 9-strong group led by Jayesh Shah (DOB: 27/10/1966) was defrauding tax by selling illicit alcohol. The fraudsters used a ring of companies used for dissimulating and laundering the funds. The network of companies and directors relevant in this matter went beyond the nine suspects. It involved a few other dozen peoples that served as previous or current directors for companies linked to the gang. VAT fraud cases have the particularity that the global picture encompasses a significant number of individuals and companies, but those acting with criminal intent are just a small number. The complex network hinders the investigation efforts and offers an efficient dissimulating scheme for the criminals.

Sanctions: Belarus under scrutiny

The European leaders reunited earlier this week in a meeting to address the issues related to the Belarus unrest. The street protests that erupted in Minsk following the elections made the situations of the current president more complicated.

The European Union anticipates in the Belarusian matter, a Ukraine-like development and consequently announced a series of potential sanctions. If the new sanctions are implemented the relationship between the Russian Federation and the EU will escalate again. Belarus served as a buffer for the last five years, allowing to bypass the sanctions inflicted to several Russian companies and politically exposed persons. When Belarus enters on the EU's sanctions list, the avenues to avoid them will go through Moldova.

This ex-Soviet country navigates since 2015 in murky waters, its leaders trying to maintain decent relationships with both Russia and the EU. Moldova had over the past five years, several money-laundering scandals and its banking system is fragile in this regard. For example, earlier this month, the Moldavian justice has frozen the assets of Victoriabank, a leading domestic bank controlled by the EBRD. If Moldova becomes the new buffer between the Eurasian Union and the EU, then the country could experience similar political unrest as neighbouring Ukraine did six years ago.