A recent Reuters article unravelled a vast network of offshore companies and doubtful individuals linked to the 2020 Beirut blast, which caused at least 204 deaths and 7,500 injuries. The investigation highlights the lack of transparency in international maritime logistics and underlines the significant exposure to financial crime risk of the freight sector. Could shipping be a tool for organised crime? Could freight be a vehicle for money laundering? How well do bankers know who the ultimate beneficiaries of their trade finance products are?

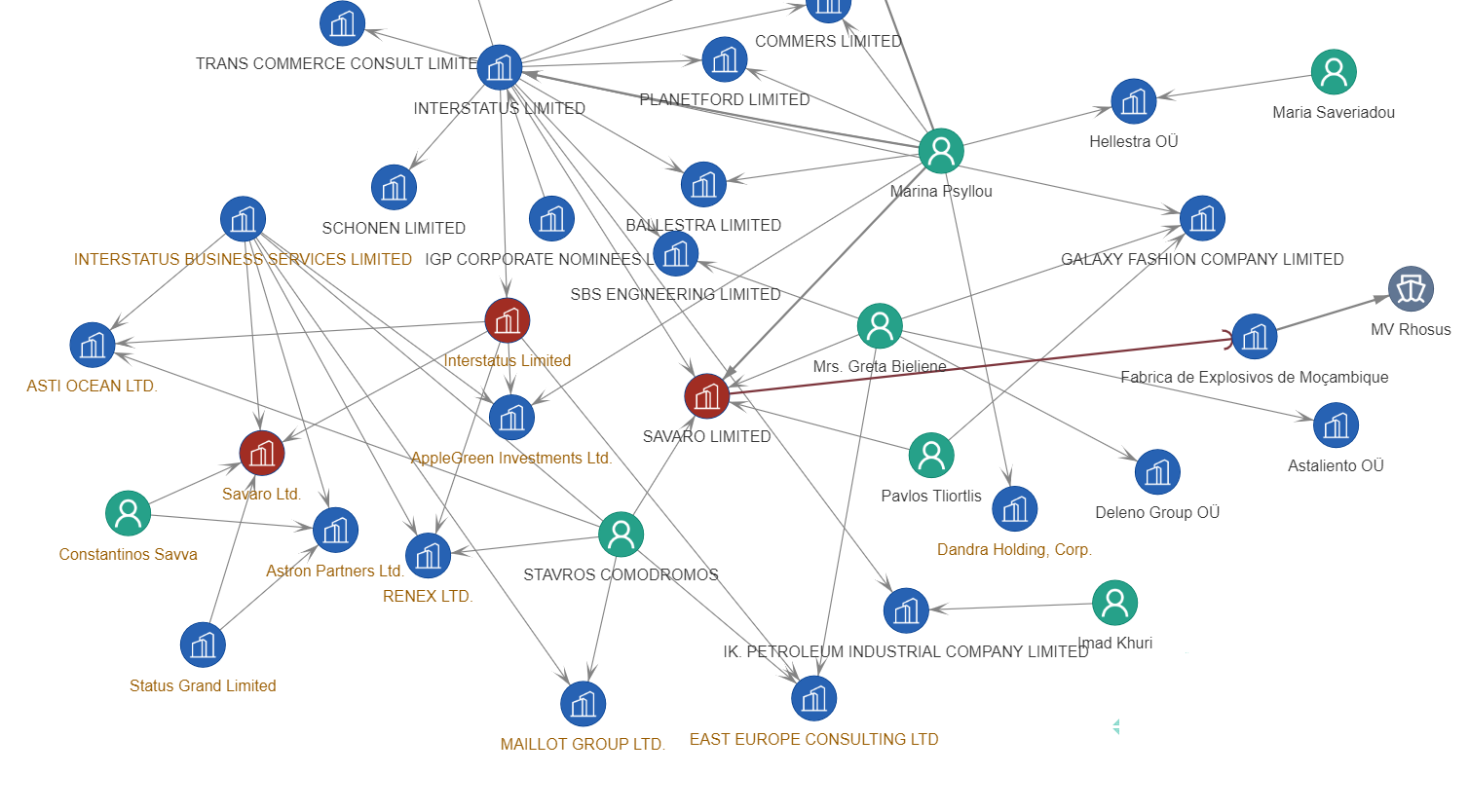

On the 4th of August 2020, MS Rhosus, an abandoned ship sailing under Moldovan flag and owned by a Mozabiquan company loaded with nitrate fertilisers, exploded in Beirut’s port. The story behind this tragedy is overly complex. The fertiliser was the property of Fabrica de Explosivos de Moçambique (FEM), a Mozambican explosive company. FEM bought the ship from Savaro LTD, a Britsh-registered company. Savaro is controlled by a holding firm called Interstatus Limited. Both Savaro and Interstatus are mentioned in the ICIJ Paradise Papers and linked to Cyprus based companies. Marina Psyllou, a Cypriot resident and Greta Bieliene, a Lithuanian citizen, serve as directors for Savaro. Interestingly, both Psyllou and Bieliene, control jointly other companies in Estonia and the United Kingdom. Moreover, Interstatus has connections with several individuals and companies which appear on the US sanction list.

There is no secret that most commercial ships are owned by holdings registered in Cyprus and Malta. Nevertheless, the MS Rhosus case underlines the opacity of the shipping sector and the lack of thorough information concerning the ultimate beneficial owners of commercial vessels.

The real issue is that global banks are behind the financing of international transactions involving freight. The trade finance divisions are providing funding for trade activities in both domestic and international markets. Thus, it is highly probable that high-street banks financed trades like those involving FEM and Savaro. The risk of money laundering and more precisely trade-based money laundering is very high in such matters. The current tools used by banks in their compliance departments do not suffice to tackle these threats.

“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the LORD, and his wonders in the deep”

Bible, Psalms 107:23-24

Focus: Khuri and Co

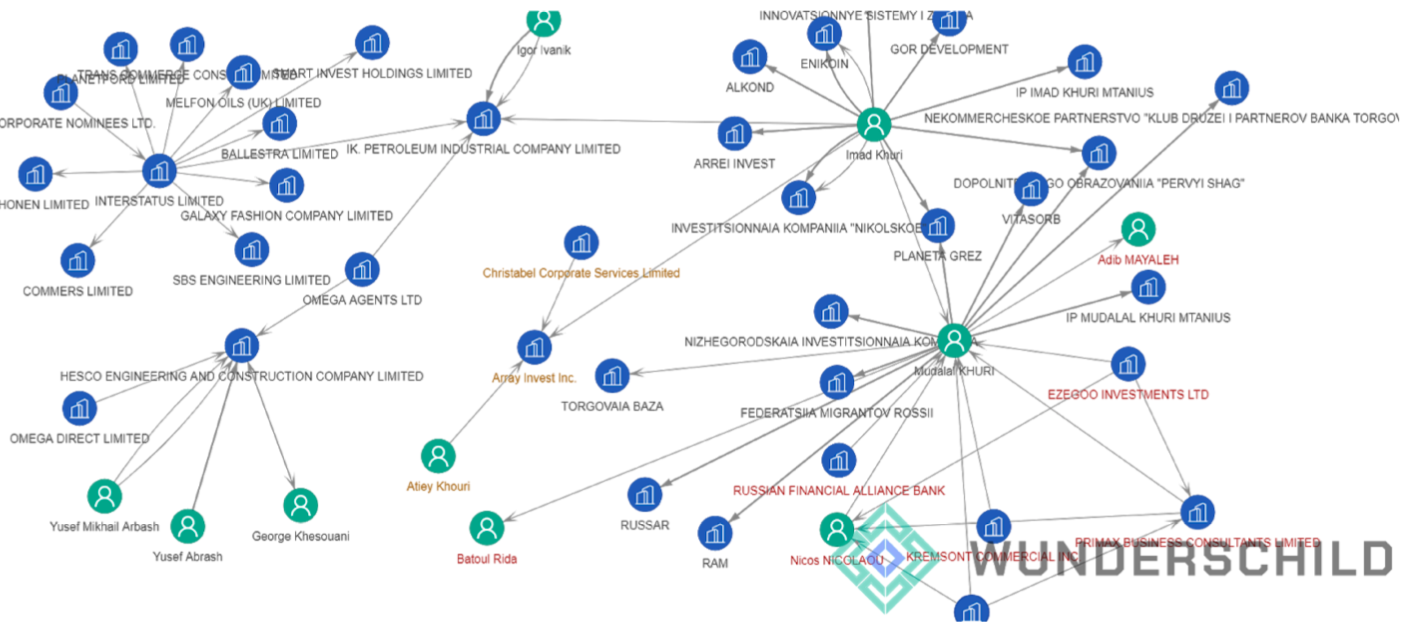

Intelligence concerning the 2020 Beirut blast points to three prominent Syrian businessmen: Imad Khuri, Mudalal Khuri and George Khesouani (Haswani). All three are connected to IK Petroleum Industrial Company a UK-based company with ties to Interstatus Limited, the company that was the previous owner of MS Rhosus. What do the three persons have in common?

- They are born in Syria and close to Bashar’s regime.

- They have Russian residences and control several companies based in the Western regions of the Russian Federation.

- They control a few firms registered in the United Kingdom.

- KKhuri brothers and Haswani are under the US sanctions.

Moreover, Hesco Engineering, a company controlled by Haswani was the real owner of the fertiliser, that was at the origin of the Beiurt blast. The feritliser was aimetd to serve to the fabrication of bombs for the Syrian regime.

Assuming the trade relevant in this matter was financed by a bank or a similar institution, it is highly probable that the financing served to launder illegal profits. It would be a classic case of trade-based money laundering, whereas criminals use a legitimate trade and the underlying banking financing to cover proceeds from criminal activities.

Extraterritoriality: No easy way out for KBR Inc.

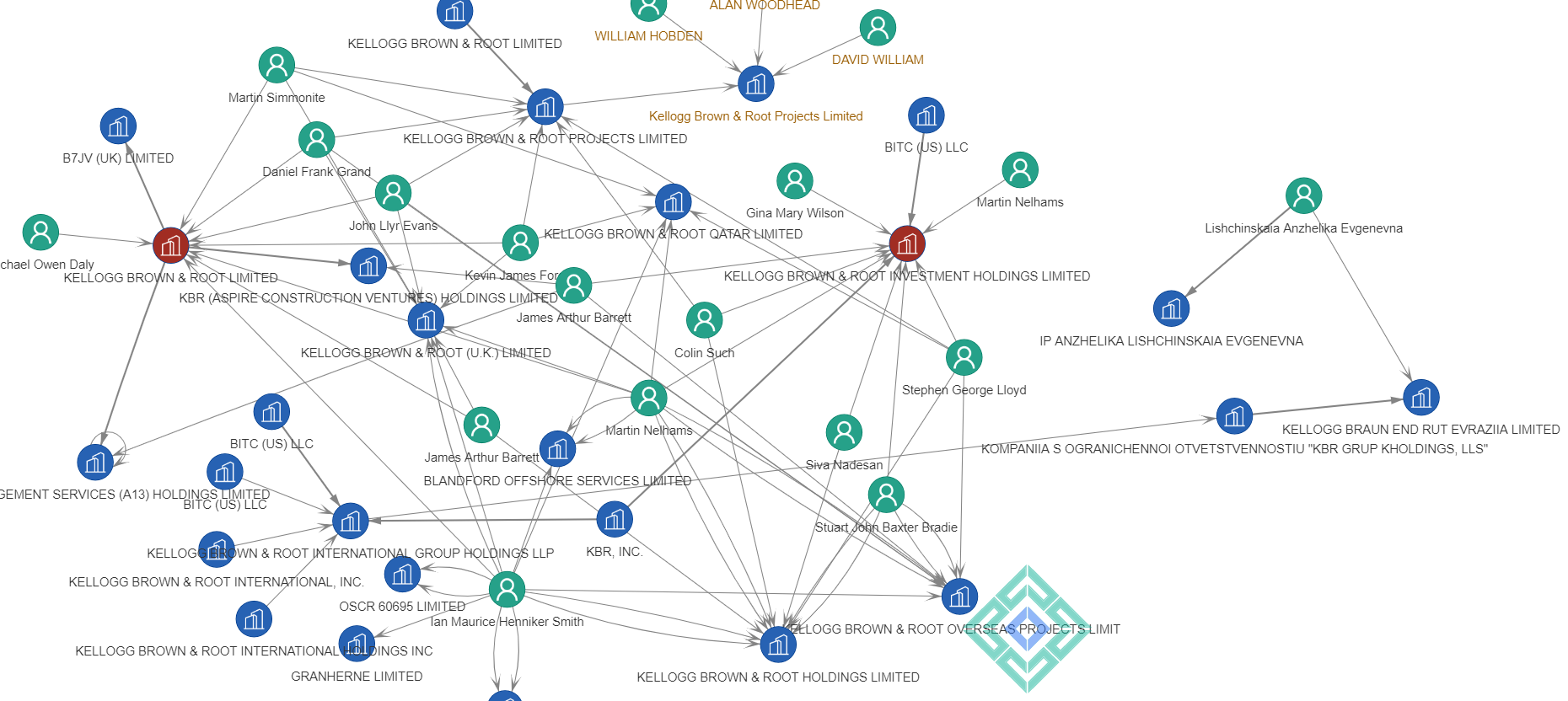

On the 5th of February, the UK Supreme Court gave a judgment on the extraterritoriality of the Serious Fraud Office’s powers to obtain documents. The matter concerned KBR, Inc. (formerly Kellogg Brown & Root), an American engineering, procurement, and construction company previously a subsidiary of Halliburton. The Supreme Court decided that the Criminal Justice Act 1987 do not have extra-territorial effects against a foreign company that does not operate in the UK. Under section 2(3) of the Criminal Justice Act 1987 (the CJA), the UK Serious Fraud Office can require a person or company to produce documents for an ongoing investigation.

Nevertheless, the US Department of Justice enforces American Laws’ extraterritoriality when foreign companies settle trades in US dollar. If a US court was asking for similar documents from a Britsh company, the outcome would most likely have been different.

Interestingly, KBR Inc has a complex structure including several holdings encompassing entities in Malta and the Russian Federation.

Word on the street: Illegal cigarette smuggling

HMRC officers arrested Svajunas Navagruckas, 51, one of their most wanted tax fugitives.

According to HMRC representatives, Navagruckas, a Lithuanian citizen was the head of an organised crime gang specialised in smuggling illegal cigarettes into the United Kingdom. The band included three other Lithuanian men, Andrej Jerofejev, 38, Vilmantas Simaitis, 48, and Martynas Nazaras, 38. Initially, gang members had fled to Lithuania but were arrested and extradited to the UK after HMRCissued European Arrest Warrants. The cigarettes were most likely produced in Ukraine or Russia and channelled in the EU and the UK throughout the Lithuanian connection.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Baltic countries entered an accelerated track of integration in the European Union. The Baltic states became success stories in the Union, adopted the Euro and joined the IMF’s list of developed countries. Despite being in the European Union, the Baltic countries still have strong economic ties with the ex-Soviet zone. After the three countries joined the Union, organised crime activities increased significantly in the region, which served as a buffer between ex-Soviet Countries and the European Union.