Six years after its relisting as a public company, ABN Amro faces significant penalties in an ongoing money-laundering investigation. The third-largest Dutch bank would follow the paths of its peers, ING and Rabobank, which were fined after being subject to criminal investigations for breaching the Dutch Act on the prevention of money laundering and financing of terrorism. How will this impact ABN Amro?

Before the 2008 financial crisis, ABN Amro was the second-largest bank in the Netherlands and amongst the top 15 global banks. At that time, the Dutch bank had big ambitions expanding not only its commercial activities but also its investment banking arm. In 2007, ABN initiated a joint venture with Rothschild bank in Paris and started to explore synergies with the Royal Bank of Scotland. By the end of 2007, RBS led a consortium of European banks that acquired ABN, thereby becoming the biggest European bank at that moment. Needless to say that the endeavour unravelled into a grim tragedy. RBS ended up near bankrupted and was acquired by the British government, while ABN, with the Dutch government’s help, was carved-ou from Fortis and recapitalised. In the aftermath, ABN Amro lost most of its investment banking activities and its overseas branches.

A new chapter in ABN history started in the early 2010s, and by November 2015, the Dutch government relisted the bank through a successful IPO. With additional pressure from investors to deliver profits, ABN entered murky waters.

In 2019, ABN’s Frankfurt office was raided by the German police in relation to the cum-ex dividend stripping scandal. In the same year, Dutch prosecutors started an investigation suspecting ABN of involvement in money laundering activities. It appeared that client screening, money laundering and counter-terrorism financing processes were insufficient. As a matter of fact, ABN established an internal financial crime detection department only by January 2019. The department expanded to 3,400 employees over the next two years. Investigators highlight two cases underlining abnormalities in ABN’s AML processes.

The first case involves FloraHolland, Netherland’s biggest flower auction marketplace, where an employee diverted funds from the company. The second case concerns a Rotterdam based metal trading company involved in a VAT carousel fraud.

The current investigation seems to be more than a slap on the shoulder. Like the ING case, ABN Amro’s directors could also be held personally liable in this criminal matter. A significant penalty inflicted on ABN will hinder its recovery seriously. The bank is already in the process of cutting more than 3000 jobs, and an additional liability will put the institution in a rough spot.

The aftermath will not look promising for the Dutch banking sector. With three leading banks thoroughly accused of wrongdoings, the Kingdom of the Netherlands faces the risk of losing confidence on the international scene.

Focus: FloraHolland

One of the cases highlighted in the ABN Amro investigation concerns FloraHolland, a Dutch conglomerate of florists. A FloraHolland employee embezzled more than 4 million euros by diverting money from the ABN Amro account to Gibraltar, gambling sites and shell companies.

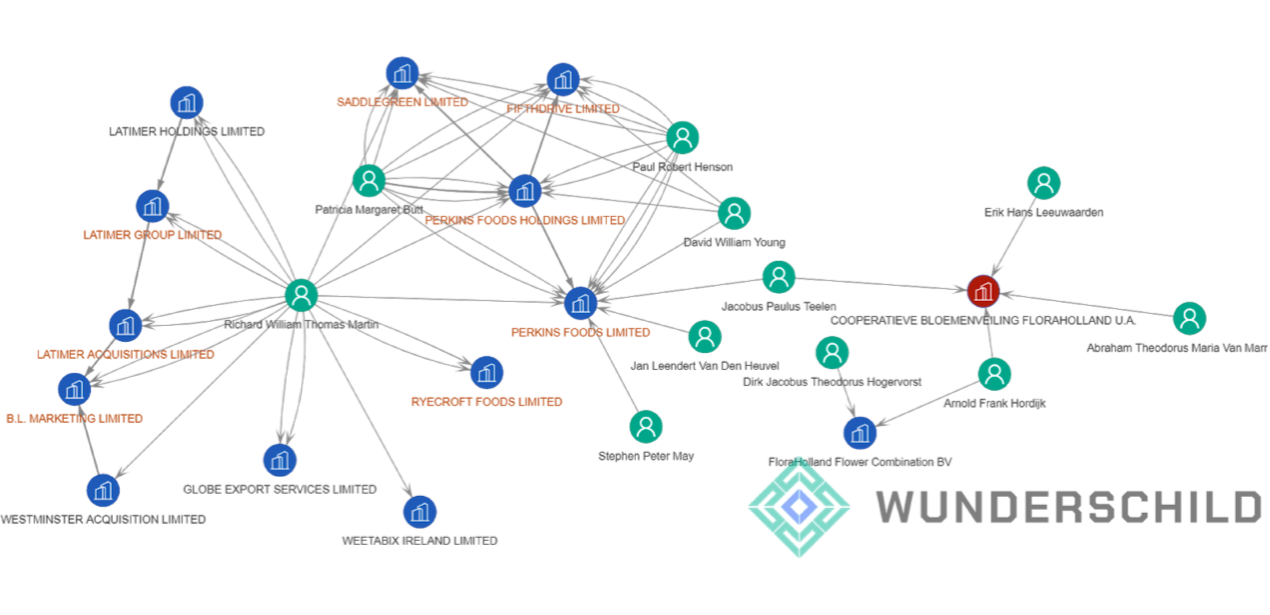

FloraHolland consolidates the activities of several flower traders. The company has a subsidiary in the United Kingdom. Jacobus Teelen, one of the persons connected to the British branch, has interests in a company called Perkins Foods Limited which had legal charges. Moreover, the underlying network around this company includes several companies bearing legal charges in British courts.

Such cases underline the limitation of current screening frameworks focusing exclusively on a standalone assessment of a client, thereby ignoring the underlying network.

Focus: VAT fraud and metals

The ABN Amro investigation brought to surface a VAT carousel fraud case concerning a bank’s client, a metal exporter based in Rotterdam.

Historically precious metals were reported in the very first cases of VAT fraud in the 1970s in the United Kingdom. The sale of krugerrand (South African gold coin, first sold in 1967) was exempted from VAT, while gold bullions were not. Therefore, criminals found an ingenious method to buy Krugerrands, melt them, sell the bars with VAT and never pay the tax back. In the 1990s, with the European Common Market’s birth, the VAT fraud with metal and precious stones increased exponentially in the United Kingdom. Gangs specialised in VAT fraud imported gold from Benelux countries VAT free and resold it in Britain, without clearing their tax liability.

In recent years, VAT fraud extended to industrial metals like cobalt or aluminium. In 2012, the Dutch authorities became aware of VAT fraud in the trade of copper cathodes. The fraud was reported to be connected to the United Kingdom and Germany.

Rotterdam is Europe’s leading port and one of the main hubs for import-export activities, thereby being a global harbour for VAT fraud. A matter judged in a Hague Court highlighted a prominent case of carousel fraud with non-precious metals. International Metal Trading BV, a Rotterdam based firm, was denied environmental permits due to its involvement in VAT fraud with metals.

Word on the street: Mafia on Youtube

Youtube has currently over 50 million active creators from all walks of life. We discussed in a previous report the cases of ex-mobsters who have become Youtubers. After being a fugitive for seven years, Marc Feren Claude Biart, a prominent figure in the Calabrian criminal syndicates, was a fugitive for over seven years. Biart, 53, was searched in the Netherlands for cocaine trafficking and found refuge in the Dominican Republic. While being in hiding, Biart had the inspiration to start a Youtube channel with his wife for sharing their extensive knowledge in fine Italian cuisine. It did not take long until law enforcement recognised him in his videos and operated his arrest in the Dominican town of Boca Chica.