Ultimate Beneficial Ownership (UBO) refers to the persons or entities that represent ultimate beneficiaries of a company. While UBO’s definition varies from one jurisdiction to another, the key challenge in designating beneficial owners relates to situations in which ownership is exercised through a network of persons and companies, encompassing a chain of indirect controls. In such cases, do data privacy regulations hinder the assessment of UBO?

Most companies have a simple and straightforward structure, thereby simplifying the obtention of data concerning ultimate beneficial owners. But, in some cases the ownership has a sophisticated structure with various layers of persons and companies domiciled in different jurisdictions. Moreover, most transnational financial crime cases involve such structures. With the 6th Anti Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD), business registers and financial institutions with commercial banking activities have the obligation to collect UBO data.

Such an endeavour seems simple in theory, but in practice for complex cases an entire puzzle should be solved in order to gather data about the relevant UBO.

Let's assume that a British company is owned by another company based in the British Virgin Islands. BVI’s business register is not open and determining the ownership of the offshore firm may require to cross-check datasets about a set of individuals that could be potentially relevant for such a case. At this point, a compliance officer may face some challenges with respect to personal data privacy regulations.

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) are the leading laws ruling the issues related to handling personal data. Both regulations are very strict when dealing with private information related persons. For the case of determining UBOs, when running searches and cross-checks about an individual, new information is created from the aggregation of puzzle solving. This new information is used in determining the ultimate beneficial ownership of a company. Pursuant to the GDPR, the persons that made the object of searches and cross-checks, should agree with such actions. Nevertheless, in such cases these persons are not clients of that financial institution or do not reside in the jurisdiction which are at origin of the assessment.

Data privacy regulations applied to the letter should be considered as a serious factor that could hinder the ultimate beneficial owners’ discovery process. Anonymizing data resulting from such data manipulation could constitute a potential solution to the problem. Nevertheless, it could make the UBO assessment useless for the KYC process .

“Privacy is not something that I’m merely entitled to, it’s an absolute prerequisite.”

Marlon Brando, Oscar-winning actor

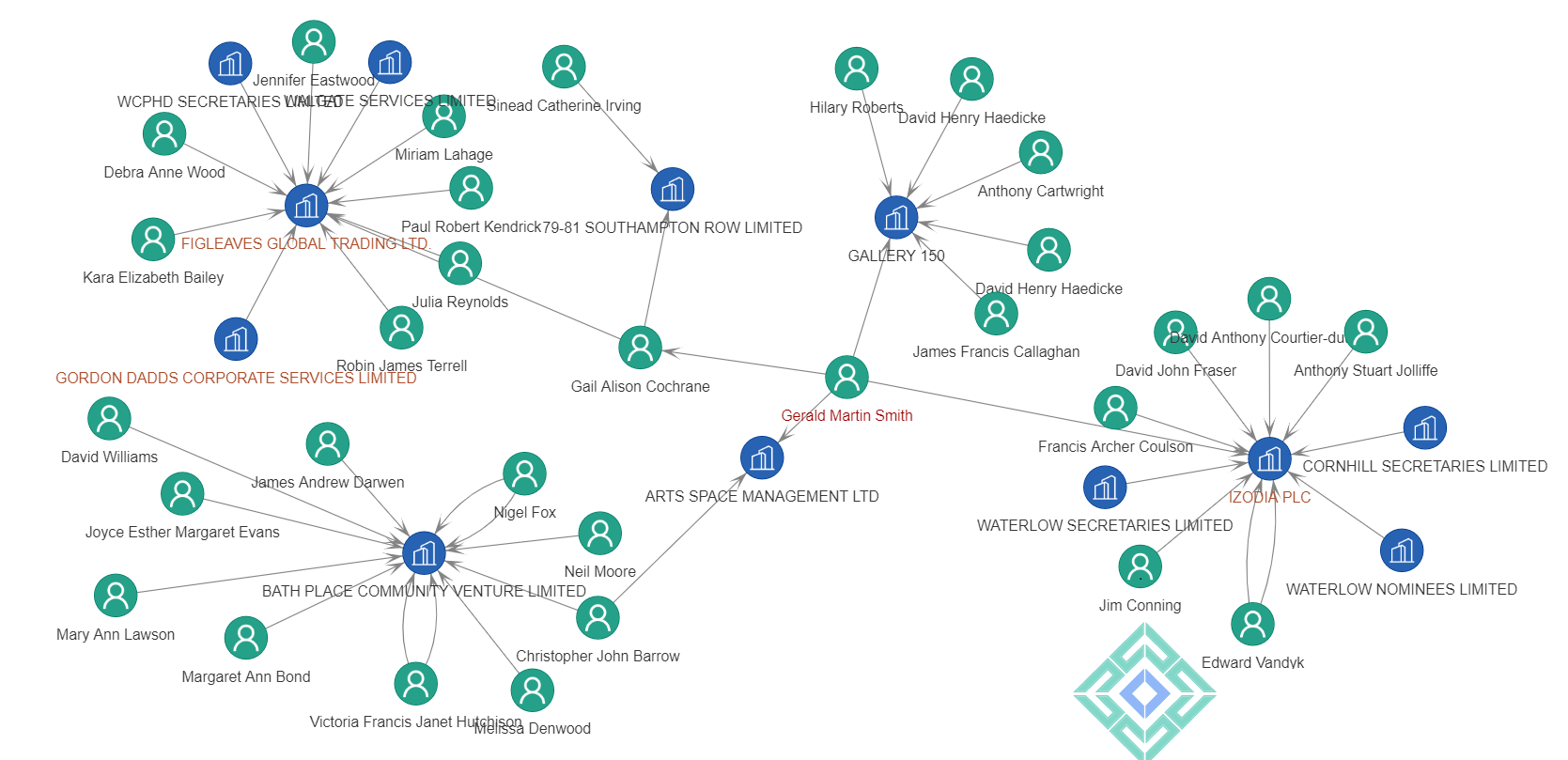

Focus: Gerald Martin Smith

Prosecuting economic crimes cases has over time become a mainstream phenomenon. From traditional organised crime to credit card skimming gangs, from politicians to prominent business persons, the arm of justice is reaching out to all social strats and people from all walks of life. Applying effectively the courts’ decisions became overly complex. Convicted criminals found avenues and leeways to avoid confiscations and paying their dues.

The case of Gerlad Martin Smith speaks for itself. The twice convicted fraudster with multiple properties in London, has spent the last decade hiding his assets from a confiscation order obtained by the Serious Fraud Office that now stands at more than 72 million GBP. In 2005, Smith pleaded guilty to rogue accounting and was sentenced to eight years' imprisonment in respect of his position at Izodia. He defrauded the LSE listed technology company for more than 34 million GBP. While law enforcement attempted to get the money back, Gerlad Smith managed to hide his assets using a network of companies based in England and Jersey. As he was struck with disqualification issued by an English court, his ex-wife Gail Cochrane helped him in his illegal endeavour. Recently a High Court judge has revealed how he hid his wealth by transferring assets to Gail Cochrane. This included establishing various companies that would control mansions and other luxury assets.

Focus: Courts duel over extradition

On 11 June 2021, London's High Court overturned the extradition request issued by a high court from Romania, one of the EU’s 27 member states. Gabriel Popoviciu, 62, a prominent ROmanian businessman was sentenced, on August 2, 2017, by the Romanian High Court of Cassation and Justice, to 7 years in prison for complicity in abuse of office and bribery, Popoviciu was living in London for several years and was placed under house arrest while appealing his case. The British court justified its decision by pointing out that Popoviciu “suffered complete denial” of his fair trial rights in Romania. The case which led to Popoviciu’ indictment had high political implications, thereby raising questions about the fairness of the defendant’s trial.

This case is a premiere and represents a direct consequence of Brexit. Until 2020, all decisions issued by a court based in a member state were enforceable in other countries of the Union, including Great Britain.

Word on the street: Organized crime infiltrated airliners

Can organised crime infiltrate multinational companies? If we take into account an article published by the BBC the answer is affirmative.

Data stemming from a classified intelligence operation published by an Australian news portal indicated that up to 150 Qantas staff had been linked to organised criminality. It is believed that motorcycle gangs infiltrated the leading airliner and were involved in drug importation and other activities.

Needless to say that Qantas’s representatives said that these claims are "disturbing". Qantas Group Chief Security Officer Luke Bramah said in a statement that law enforcement agencies have not raised concerns about Qantas's vetting or background checking processes.

Most corporations spend massive amounts of money for screening and assessing clients. Nevertheless, when hiring new staff, especially in low-entry jobs, less is done. Reports from various countries show that many other sectors including banking and financial services were infiltrated by organised crime.