The financial crisis of 2008 destroyed people's confidence in the investments sector. The COVID pandemic empowered laypersons to become active players on the financial markets, and retail liquidity is pouring in the leading stock exchanges. Thus, the stock market and technology shares, in particular, experienced a Super-V recovery after the March crash amid a global economic contraction.

Are there hidden risks behind the Techmania? Is this new bubble a time bomb?

The pandemic outbreak was the right moment for financial independence gurus and antisystem advocates to push individuals to reconsider the way they manage their monies. Retail investors hold the irrational belief that investing in innovative companies amid an unprecedented crisis is the right thing to do. Thus, a new investment rush in tech shares was born like Tulipmania in the 17th century and Bitcoinmania of 2017. Moreover, digital investment platforms allowed individual investors to bypass the traditional infrastructure of the financial sector, to make their own decisions and to build their trading portfolios solely.

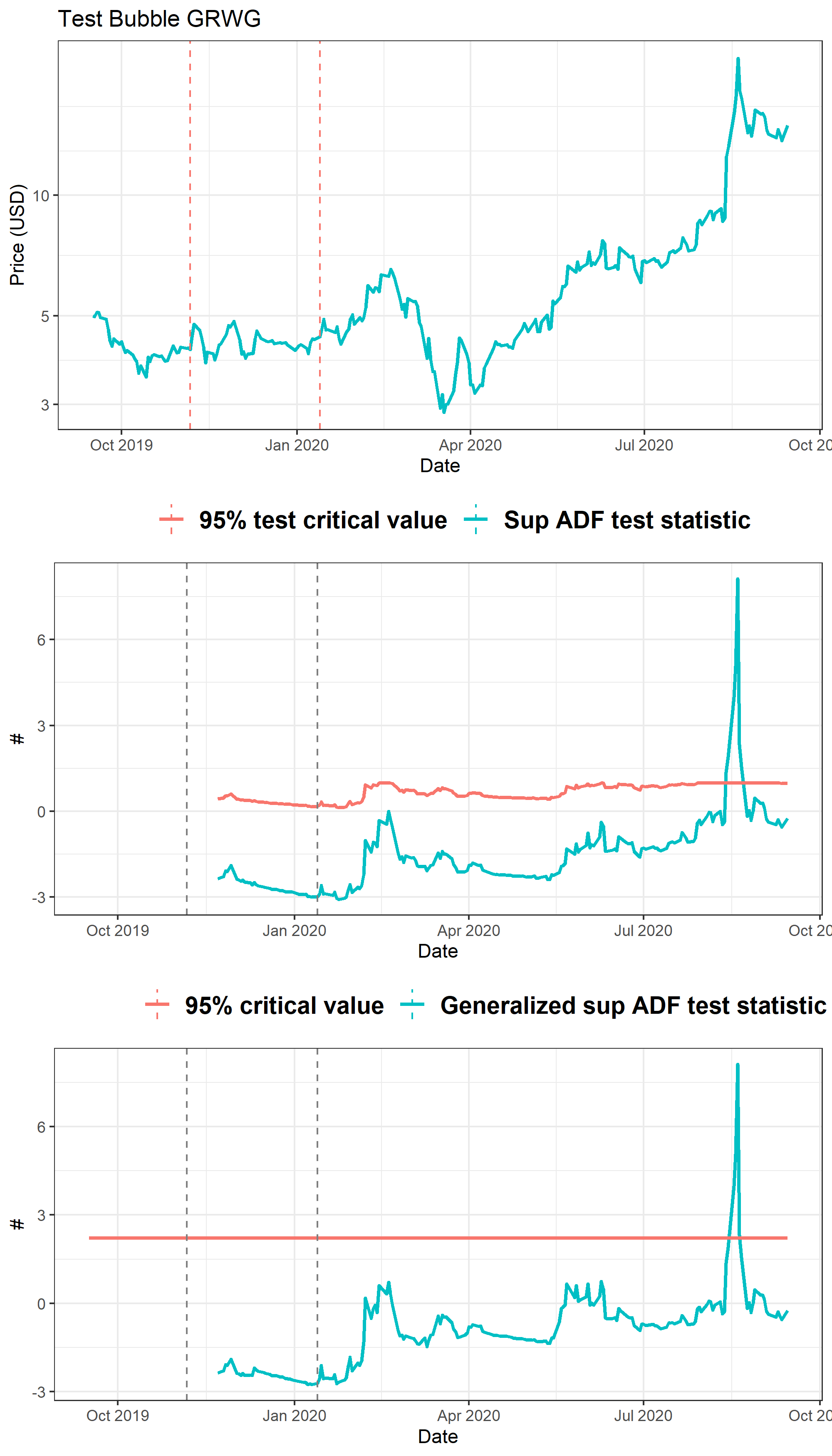

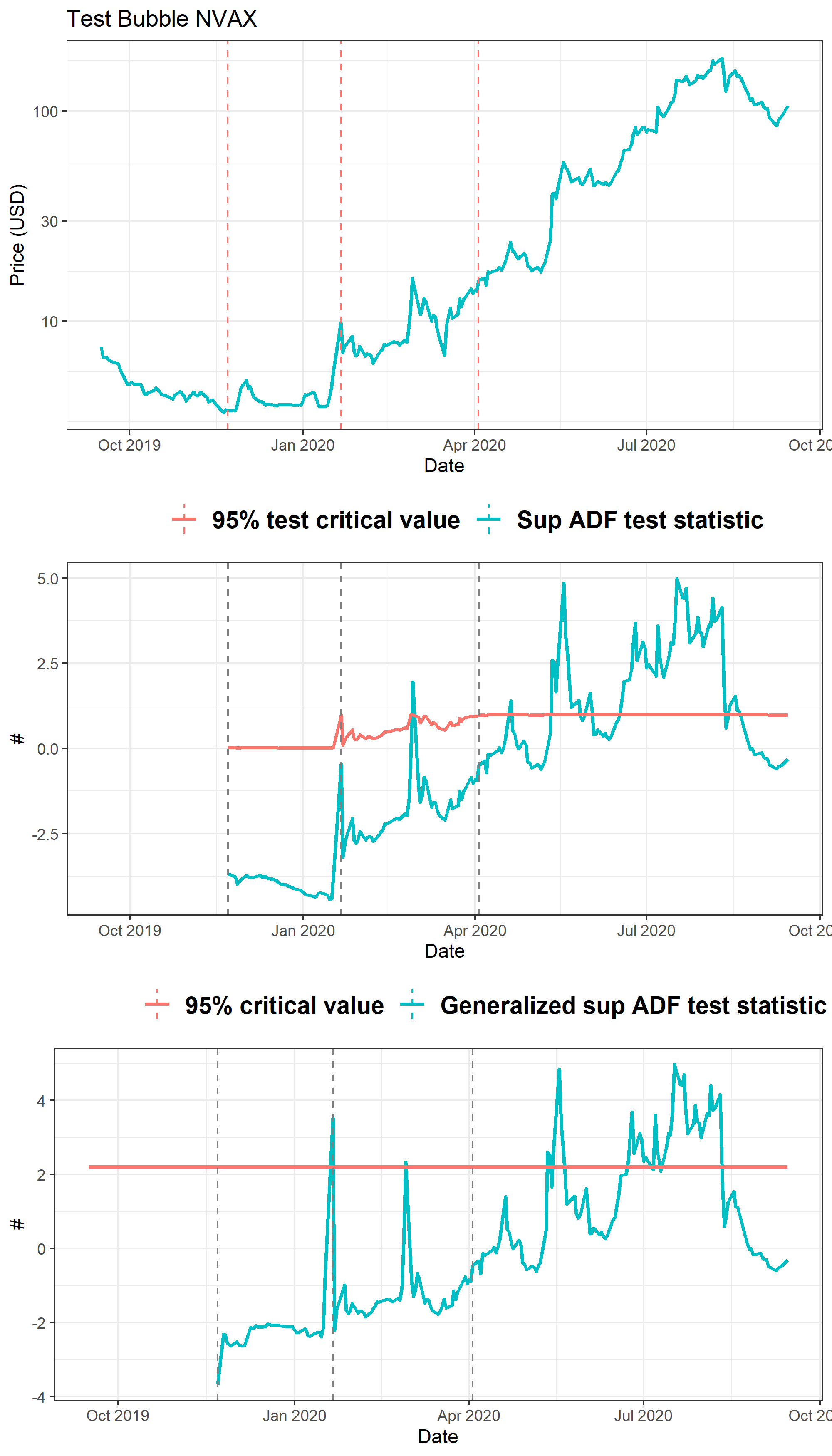

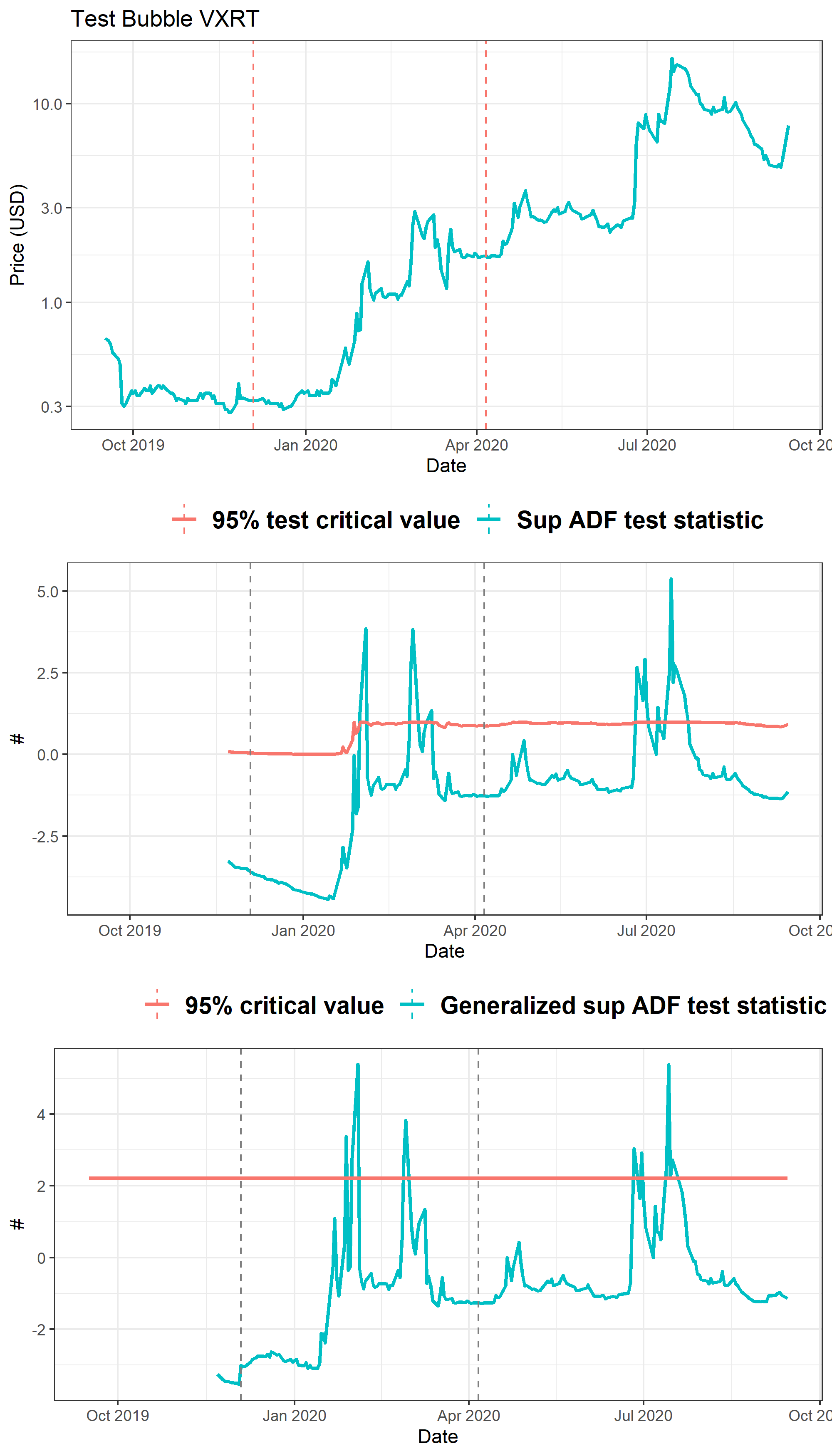

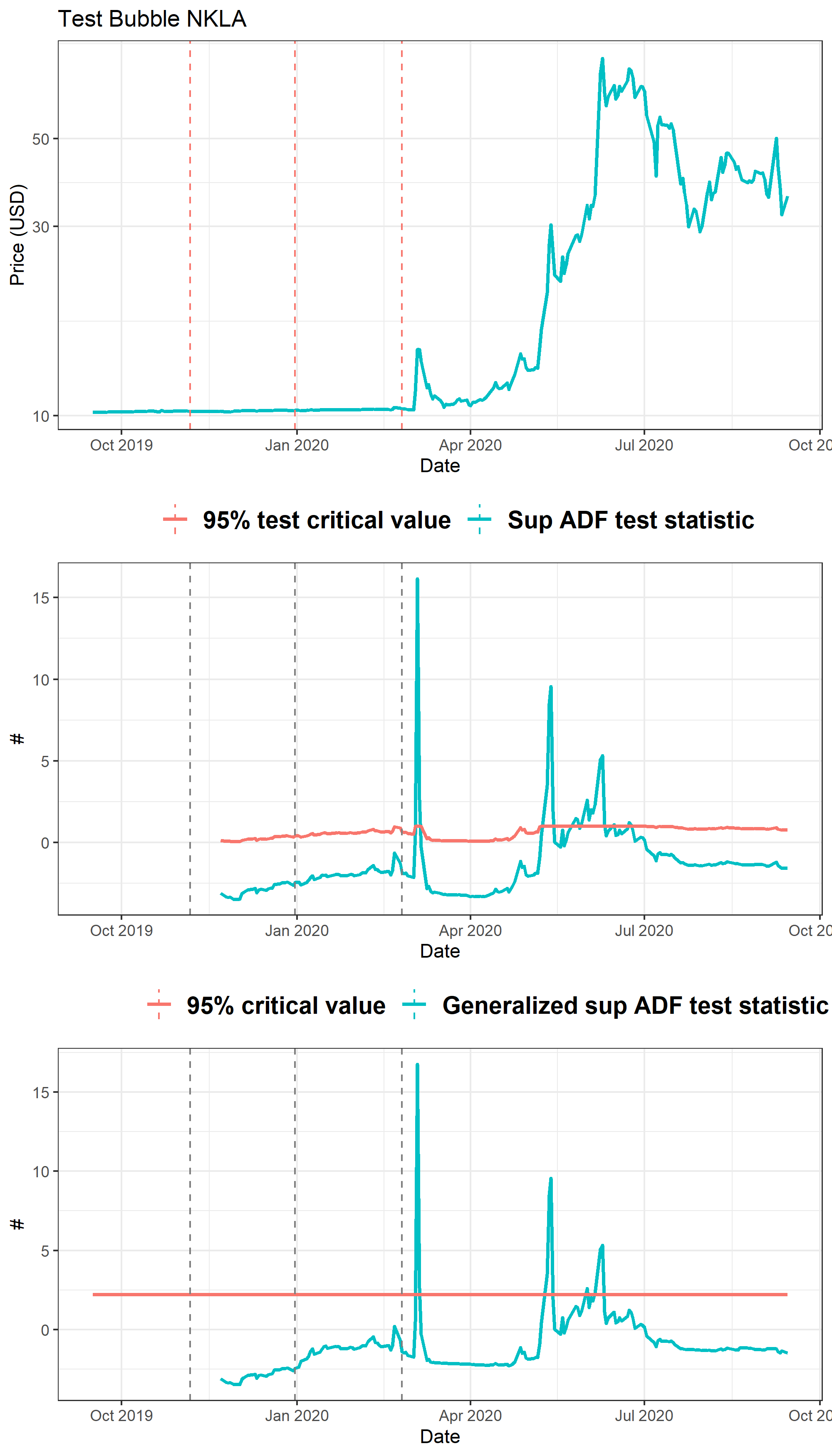

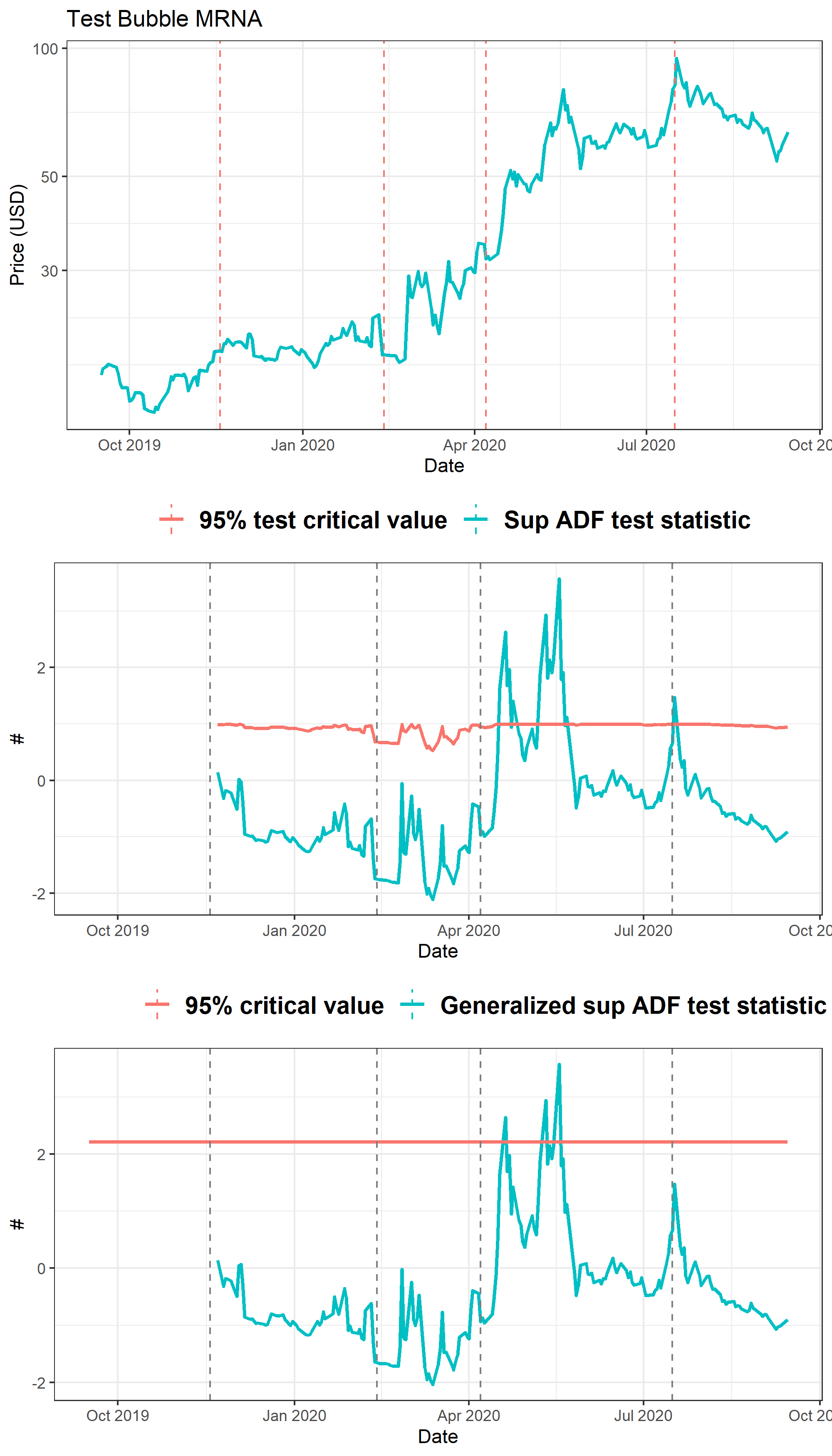

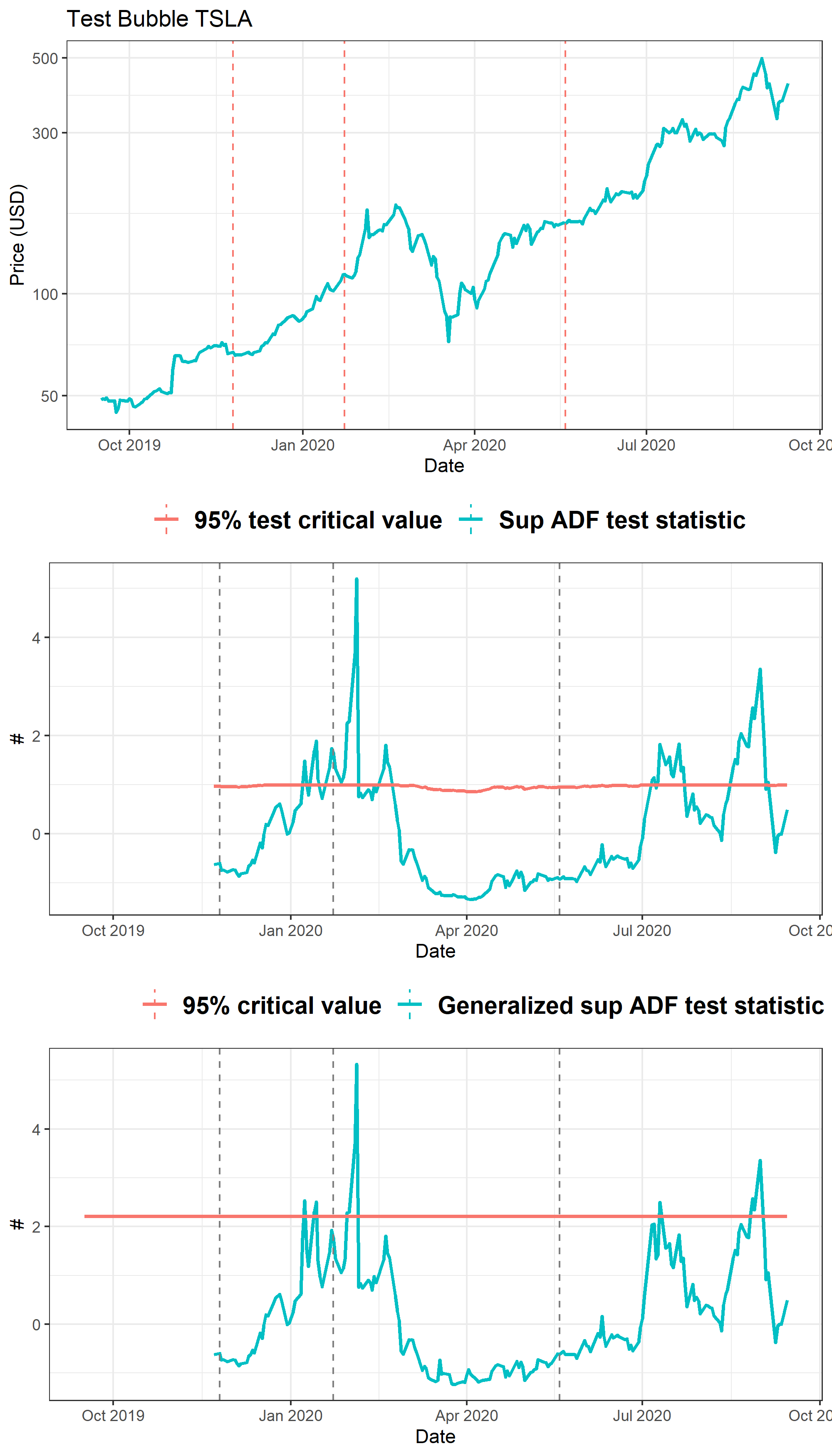

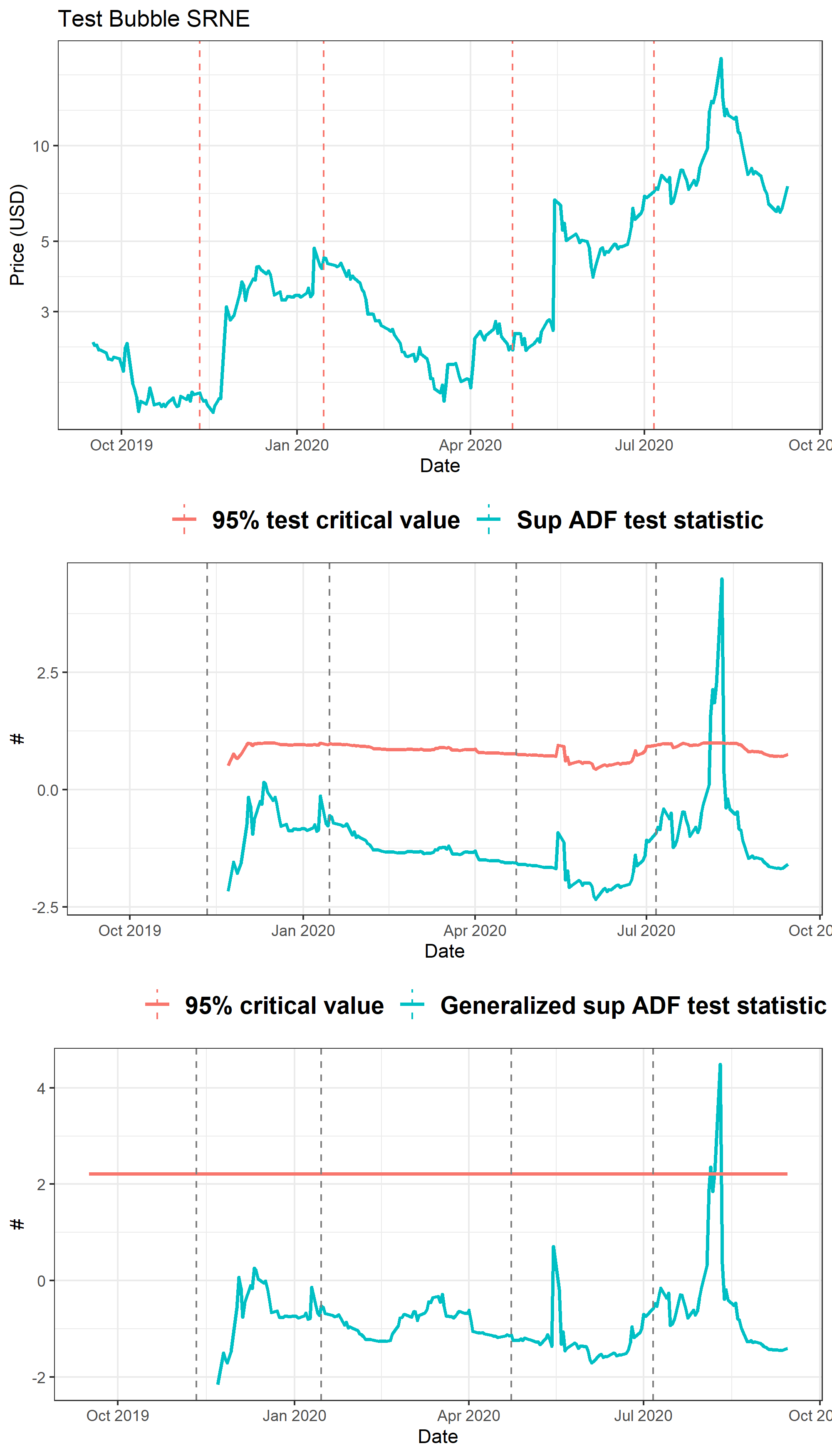

Statistical tests1 indicate that since March 2020, a significant number of Nasdaq stocks experienced a bubble characterized by a hyper-exponential price growth. Companies like Tesla, Moderna or Nikola saw the value of their shares increasing several times in only a few months. Moreover, this growth came during a period when most economies went through a massive GDP contraction. In a few cases, shares' prices bolstered even though companies showed modest revenue figures.

Nasdaq stocks that experienced in the past bubbles were the object of class actions filed by disappointed investors. The narrative was that those firms overstated the growth perspectives and misled the shareholders. These types of class actions frequently occur in the case of early-stage firms with low revenue depending on a patent or a product requiring FDA approval.

All the conditions mentioned above are met for most stocks that went through price bubbles over the past six months. Not all COVID remedies will work, and not all tech firms will flourish. The Techmania bubble will burst in the end. Thus, the late investors in those stocks may face significant losses and disillusions. We already see in short-sellers' market researches the cradle of future court lawsuits against many of these tech companies. Class-actions or more precisely, global class actions could flood the judicial system in 2021, unleashing the anger and the dismal agony of marginalized individual investors.

| Company name | Ticker | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Tesla | TSLA | Tesla is world biggest automotive manufacturer in term of market capitalisation. |

| Nikola Corporation | NKLA | Nikola aims to produce zero-emissions vehicles including a hydrogen-fuelled truck. |

| Novavax | NVAX | The company in engaged in the race for a COVID vaccine. |

| Sorrento Therapeutics Inc | SRNE | The company develops a Covid-19 saliva test. |

| GrowGeneration Corp | GRWG | The firm provides supplies for growing cannabis. |

| Vaxart Inc | VXRT | The company in engaged in the race for a COVID vaccine. |

| Moderna | MRNA | The company in engaged in the race for a COVID vaccine. |

“What really matters is an awareness of how greed and fear can drive rational people to behave in strange ways when they gather in the marketplace.”

Joseph de la Vega, Confusion of Confusion

Mini-bonds and beyond

Mini-bonds are unregulated illiquid debt securities issued generally by small businesses, start-ups or firms that cannot access the traditional financing avenues. Over the past five years, mini-bonds were intensively marketed to individual investors, especially in the United Kingdom. 2019 was a lousy year for this market, because most British companies that issued and sold mini-bonds went bust, leaving the investors with huge losses.

One prominent case concerns the Carlauren Group, a care home firm which used money from individual investors to expand its operations. The company collapsed last year, after raising 76 million GBP by issuing mini-bonds. In the aftermath, Carlauren went bankrupt, owing to investors over 40 million GBP. Recovering this sum is a difficult task because Carlauren had an overly complex structure with a few dozen companies interrelated in a sophisticated network. A holding firm Carlauren International Holding was registered in Jersey. The key persons running the operations were the CEO Sean Gerrad Murray (DOB: March 1966) and Richard Michael Baker (DOB: August 1962). Both they were stakeholders in the primary firm and in a myriad of companies which operated the care houses and other related business.

The CEO had a long entrepreneurial history. He was in 2011, the director of a company called Appy Brands Limited, previously known as New Orbit Funding. The company2 allegedly sold bogus investments in Detroit properties to individual UK-based investors. There was no happy ending for those people, and most likely, it will be no happy ending for Carlauren's investors.

The cases concerning "mini-bonds" are just the tip of the iceberg. Many other schemes involving unregulated investments proposed to the public appeared amid the coronavirus pandemic. Some are collateralized by real estate, while others are based on the tokenization of illiquid assets. The valuation of such instruments is involved; the firms behind these schemes do not always have appropriate experience in the financial sector. Most probably, 2021 will bring a new wave of unfortunate investors in courts to look for justice.

Risk: Consumer investment market

The coronavirus outbreak brought an unexpected and somewhat counterintuitive phenomenon. Despite a severe economic crisis, retails investors are placing significant amounts of liquidity into traditional investments and not only.

Therefore, the Financial Conduct Authority, the leading UK financial markets watchdog started to take a closer look at the consumers' investment markets. This initiative aims to protect members of the public and to reduce the potential losses caused by risky investments or fraudulent schemes. Investments in unregulated or opaque markets are the primary concern. While traditional financial markets including stocks, bonds or forex have a certain degree of efficiency, some modern investments including mini-bonds, early-stage private equity, cryptocurrencies, tokenized assets, or property-backed notes bear significant risks for averagely informed individuals.

To be able to make a qualified investment decision, investors need to understand the instruments they are buying. The more complex an investment is, the less likely it is for a layperson to comprehend it.

Thus, the main question the FCA (and other regulators) should address is whether a layperson can be qualified as an informed investor. If the answer is affirmative, what are the necessary conditions to qualify a member of the public as an informed investor? Answering these questions could solve two problems.

On the one hand, it can reduce the number of abuses and frauds observed over the past years. In many cases, retail investors bet their monies euphorically on dream-selling investments, without having any clue about how those markets work.

On the other hand, it will reduce the pressure on courts, which face the anger of deceived investors.

Word on the Street: Mafia on Wall Street

Two decades ago3, in September 2000, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission provided an insightful testimony concerning the involvement of organized crime on Wall Street. Since the late 1970s, associates of New York's underworld known as "La Cosa Nostra" infiltrated the Wall Street-based investment firms. The involvement of the "Five Families" in financial crimes increased during the 1990s, the Bonanno and Genovese crime families being the most active in these regards. Consequently, a significant number of market manipulations and penny stocks scams were investigated by the SEC, the U.S. leading financial watchdog.

That testimony underlined a turning point in the evolution of organized crime. The "mob" and other syndicates switched their modus operandi from traditional "blue-colour" crimes to more sophisticated non-violent frauds. Since then, the frequency, the severity, and the complexity of scams on financial markets did not cease to increase.