The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists unveiled the latest chapter of its crusade against the world's most rich and powerful alleged tax offenders. Many compliance officers are cheering on social media for the Pandora Papers, embracing the release of leaked files resulting from breaches in data privacy. Is this the end of offshores? Or maybe is the end of data privacy?

Data privacy is essential.

Paradise Papers represent 2.9 terabytes of leaked data, including more than 11.9 million files. Such a massive amount of data extracted from organisations by breaching data privacy systems raises serious concerns about the integrity of digital infrastructures used by certain institutions. While many compliance officers working for high-street banks applaud ICIJ’s actions, they should be aware that their institutions are not immune to such breaches in data privacy. This attitude creates an unprecedented double standard.

On the one hand, hacking data from certain firms based in tax havens is all right. Thus, Paradise Papers is nothing more than a sandbox for testing the protection of sensitive data concerning high net worth individuals. But, on the other hand, the regulations for data privacy applied to onshore institutions have become stricter.

Therefore, “the largest investigation in journalism history exposing a shadow financial system that benefits the world’s most rich and powerful” lays the foundation for a testing environment that enables hackers and activist groups to leak private data without directly affecting the infrastructure on which they run, but with a massive impact on the custodians of those data.

Transparency is an illusion.

Why does privacy matter in the world of finance? Why is transparency illusory?

The ICIJ's investigations aim to break the opacity of tax havens and increase the transparency of the financial system. Their main narrative is that only a transparent global financial system can curb tax evasion and financial crime. In theory, everything sounds good, but reality rarely matches theory. The financial system consumes two primary commodities: information and time. Information and especially private information, holds intrinsic value. Financial institutions use data and its underlying value to serve their clients. If all information becomes public and all financial infrastructures are transparent, then all services proposed by the different players in the financial industries would become worthless. People have used financial services since immemorial times for the simple reason that the providers of those services were able to deal with information and especially with private information. A fully transparent system that services fiat money would mark the end of banks and financial markets.

Taxation is complex

Not all people using offshore infrastructures are criminals or tax offenders. On the contrary, most individuals and companies using such services want to be on the right side of the law. In the era of decentralised finance, criminals would care less about establishing companies in offshore jurisdictions and would opt for simulating the funds through many layers of transactions.

Moreover, the separation line between tax compliance and tax fraud is very murky. Thus, a few legal options are available when a company or an individual looks for leeways from the regular avenue of paying in full their tax liabilities.

- Tax optimisation adjusts the various financial metrics representing the base for tax levies to minimise the total tax liability. A simple example is to use debt in corporations as a tool to reduce the corporate tax bill.

- Tax arbitrage profits from differences between countries or regions in terms of taxation for the same transactions.

- Tax avoidance is the practice that employs legal methods to reduce tax liability by claiming deductions or refunds aggressively. In addition, tax avoidance can use sophisticated structures like offshore holdings and structured financial products like insurance or derivatives designed to enhance tax avoidance.

Tax evasion is employing illegal methods to reduce partially or totally tax liability or to access fraudulently tax reimbursement from national tax offices.

“If someone wants to open this Pandora's box and deal with it, all right, go for it then.”

Vladimir Putin, President of Russia

Focus: Mario Vargas Llosa

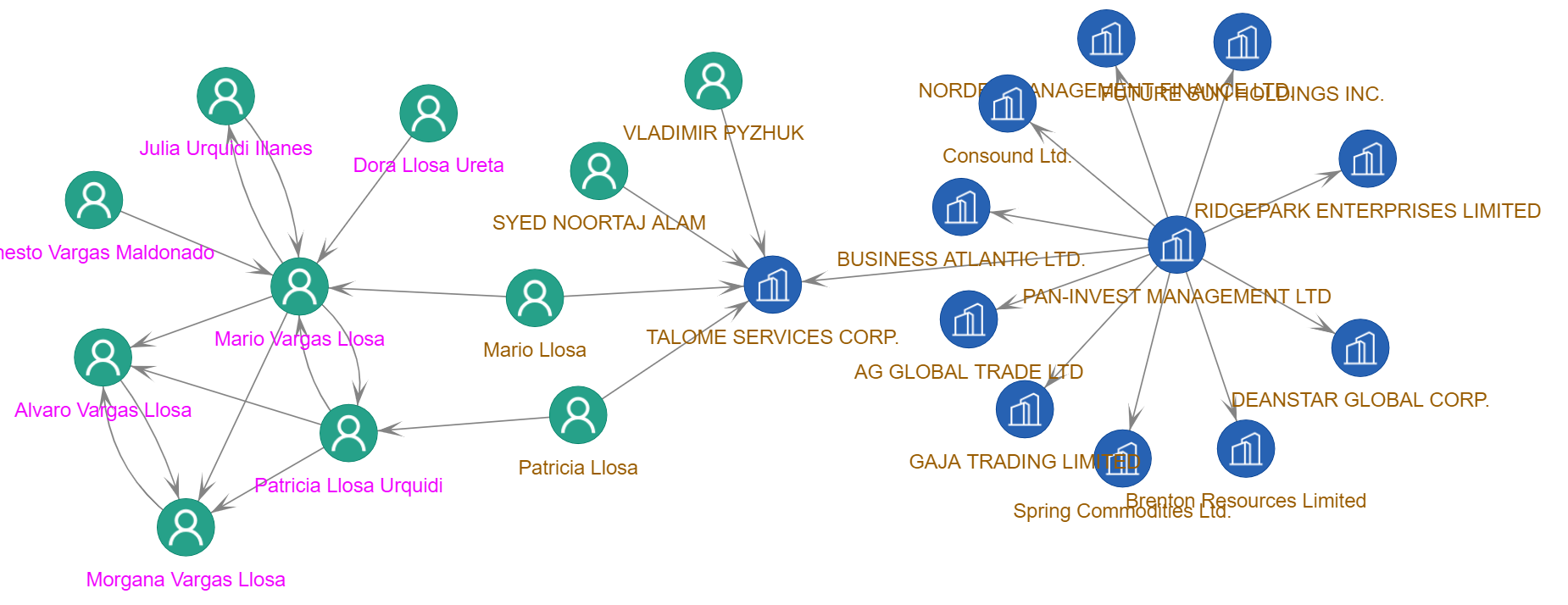

Mario Vargas Llosa, a prominent Peruvian writer, former politician and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, is one of the key figures in Pandora Papers. The ICIJ investigation shows that Vargas Llosa has used a “BVI-registered corporation to invest royalties from his writing”. The Spanish newspaper El País mentioned that the company is called Melek Investing Ltd., but a representative of Llosa indicated that the firm was disclosed to tax authorities.

Before his commercial success as a published author, Llosa had a significant political career. Interestingly, his political career did not raise any suspicions concerning financial malversations. Llosa also appeared in the previous ICIJ investigation. The Panama Papers show that Llosa and his ex-wife Patricia had a company called Talome Service registered in Seychelles. Such “revelations” are nothing more than cases of high net worth individuals following traditional avenues of tax optimisations. Given the profiles of such individuals it is high unlikely that such schemes were not bulletproofed by legal advisors.

Word on the street: Miami is the new Marbella

Since the early 2000s, Spain’s sunny beaches and, in particular, Marbella became the place to be for the creme de la creme of organized crime. English gangsters with thick Cockney accent, Russian bandits, wearing tattoos with religious themes and Italian Mafiosi transmogrified into real-estate investors cohabit in perfect harmony. Many other groups, including Albanians, Montenegrin, Georgians, Chechnians and Magrebian gangs, joined the Gotha of crime in Marbella. The pandemic outbreak and the extended lockdown periods pushed criminals to look for other places under the sun.

Florida has always been an open territory for the major crime syndicates in the US. The five New-York families, the Colombian Cartels or the Cuban gangs, shared since the late 1970s Florida’s underworld. In the late 1990s, Russian gangsters joined the party. Throughout the pandemic outbreak, Florida has kept its economy open. Thus, the nightlife businesses constituting the playground of organised crime, continued to operate over the last two years. While other states and European countries hindered traditional criminal activities through lockdowns, Florida attracted crime figures from all around the world.