The three letters that make every investor dream are, in reality, more cryptic than one could imagine. In the age of globalisation, when most businesses become highly interconnected, assessing whether a company is prone to sustainability becomes tricky. So, how transparent are the ESG ratings? What is the role of ESG compliance?

Green investing is not trendy anymore because it has become a regular thing. The pandemic and the governmental policies for green recovery accelerated the migration of investors from traditional portfolios towards ESG funds. A recent Bloomberg report shows that the global ESG investing industry is on track to exceed USD 53 trillion by 2025, representing more than a third of the USD 140.5 trillion in projected total assets under management. The world of business is highly interconnected, and companies have a high level of interdependence. Therefore, separating “good” from “bad”, “green” from “dirty”, and “sustainable” from “unsustainable” is a complex task. One company may tick all boxes of an ESG assessment, but what about its subsidiaries, suppliers, or leading clients? Sustainability is more than hitting a few metrics and is more about proving that a company and its connected parties generate positive externalities. If one-third of the investments in 2025 will be ESG related, what the other two thirds will be? Can one side of the economy be sustainable, green and ESG rated, and the other side be the exact opposite? For sure, it cannot.

ESG rating is not about a company but about the company and its connections. Sustainability does not concern just the company business but also includes its spillover effects. Thus, gathering the fully-fledged picture of a company and its underlying network (Know Your NetworkTM-KYN) is the only efficient way to provide a well-rounded profile of a company and its potential spillover effects.

The ESG rating agencies seem to commit the same fallacies, credit rating agencies did. First, an ESG rating is given against a fee, thereby hindering the independence of the rating agency. Second, rating agencies are, in many instances, underwriters for the rated companies. Last but not least, ESG rating agencies are looking for growth and aim to include as many counterparties as possible in their scope. Finally, ESG compliance is emerging to push corporations to be more transparent to ensure compliance with legislation and developing moral and ethical expectations.

The ESG rating process is far from being transparent as it deals with many non-quantifiable subjective qualitative aspects. Moreover, ESG does not concern only a firm but also encompasses its environment and connections. Sustainability is not about the individual; it is more about the group; it is not about the corporation but about the network behind the corporation; it is less about the standalone performance and more about long term impact. Therefore, KYN is the appropriate tool that can close the gap in terms of the conceptual soundness of ESG ratings.

“ESG fund managers are capitalists. They are investing to make money — they might do some good, but that good has to lead to return”

Michael Martin, private client manager with Seven Investment Management

Focus: Rajanish Garibe

You may ask yourself why there is a shortage of workforce. The answer is simple. In modern history, it has never been easier than today to get money for free from governmental agencies. The spread of the coronavirus pandemic is surpassed only by the rampant epidemic of furlough fraud.

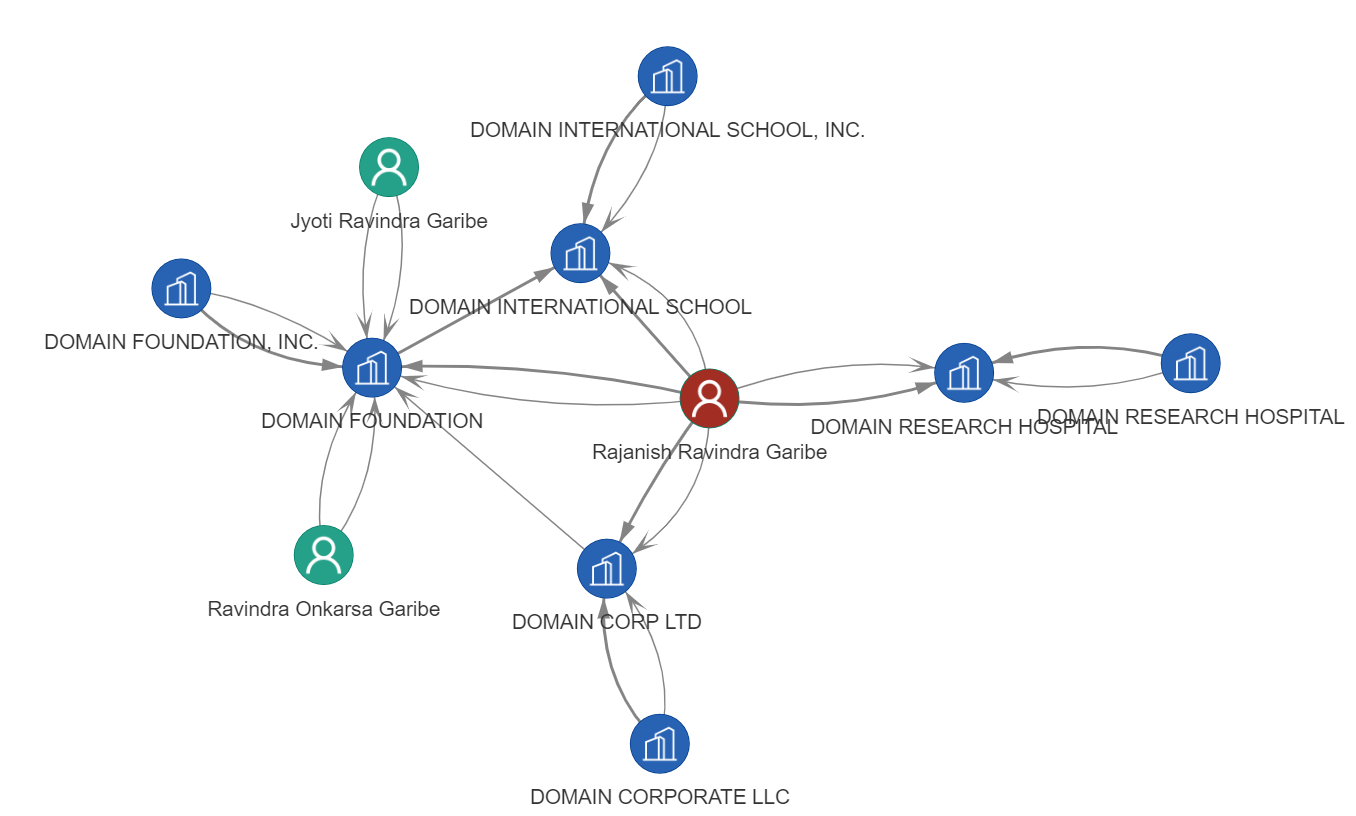

Financial Times highlighted the case of Rajanish Garibe, a 44-year-old Indian national, who used four companies to access furlough funds. British tax officials have managed to seize GBP 26.5 million from Garibe, who engineered a complex network of companies to defraud the government using the GBP 70 billion furlough scheme introduced in response to the pandemic. Garibe allegedly invented seven employees and obtained thousands of national insurance numbers that were either fake or stolen to apply usefully for furlough funds.

Garibe controlled four companies, including an IT services company, a corporate charity, a research hospital and a Jain religious institute. Each company was owned by a holding established abroad, mainly in the United States.

Focus: Mann, Dhillon and Bharj

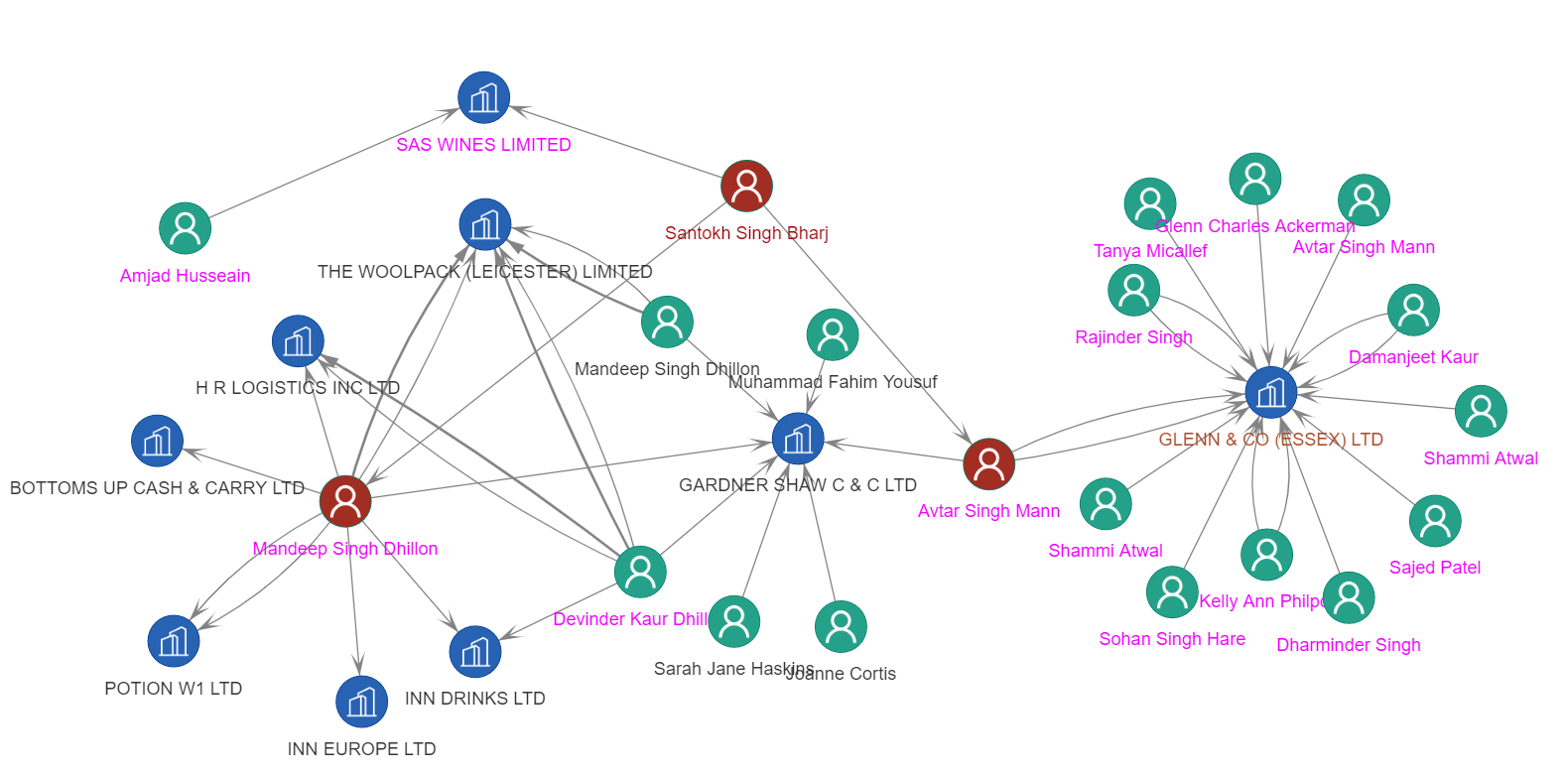

Mann, Dhillon and Bharj is not the name of a law firm, but a group of criminals specialised in laundering money from the sale of non-duty paid alcohol. The Southwark Crown Court found guilty three individuals: Avtar Singh Mann, 50, Mandeep Singh Dhillon, 40 and Santokh Singh Bharj, 54, of laundering GBP 25 million. They have been sentenced to more than 11 years in jail.

Mann and Dhillon were the directors of two cash and carry companies in Barking. Mann controlled, amongst other firms, Glenn & Co (Essex) Ltd in River Road and employed Bharj, who owned a wine company. Dhillon held Gardner Shaw C&C Ltd in Thames Road. The vast network of firms controlled by the three criminals allowed them to move millions of pounds through the bank accounts of shell companies set up to launder cash.

Word on the street: Laundering money from drug trafficking

French police arrested six men from the Pakistani community. They are suspected of being involved in the laundering of 70 million euros from drug trafficking. During the arrests, 675,000 euros in cash were found by law enforcement in a cellar converted into office space. At the same time, 825,000 euros were seized from the accounts of fictitious companies. The investigation started in 2019 revealed that the group structured different financial schemes to channel the proceeds of crime.

The six men aged between 20 and 40 controlled various construction businesses in Dubai and mobile phone shops. The group used money mules from Spain to insert cash into companies owned by straw managers. The cash was initially directed towards the directors of construction companies, who used it to pay their employees or for certain services. The scheme encompassed over 20 companies that received payment from abroad, especially from Spain. The laundered money was then redirected to mobile phone shops. The funds were then sent abroad through a compensation system, mainly to Dubai, where the drug traffickers eventually recovered their earnings.