The FBI has recently raided Washington and New York properties linked to the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, a close associate of President Putin. In 2018, the U.S. Treasury Department added Deripaska and six other Russian billionaires to its sanctions list. The love story between Western countries and oligarchs’ money seems to have reached the end of the line. Is this the twilight of the oligarchs?

Before analysing the current situation, some questions need to be clarified. Who are the oligarchs? What is the origin of their fortune?

The roaring 90s

Oligarchs made their fortunes throughout the 1990s during the obscure privatisation process that took place across all countries of the ex-Soviet bloc. Privatisation refers to the transfer of ownership of businesses or properties from a government or a governmental agency to a privately owned entity or private individuals. A massive wave of privatisations occurred in the countries of the Communist bloc during the 1990s and more gradually in China over the past two decades.

As expected, the privatisation process in Eastern European countries did not manage to transform government-owned firms into efficient and innovative private entities.

The linkage between public companies and politically exposed persons made ex-Soviet countries unsuitable candidates for rapid privatisation. The fast-paced privatisation involved many auctions of publicly-owned companies, whereas networks of governmental officials, plant managers and their criminal allies had the upper hand. Corruption was undoubtedly an issue, and inexperienced East European market regulators could not implement efficient policies to control fraudulent privatisations. The controversial privatisation process generated a new form of economic paradigm: “the grey capitalism". In the 1990s, privatisations were fertile ground for unscrupulous and fearless businessmen who were later known as oligarchs.

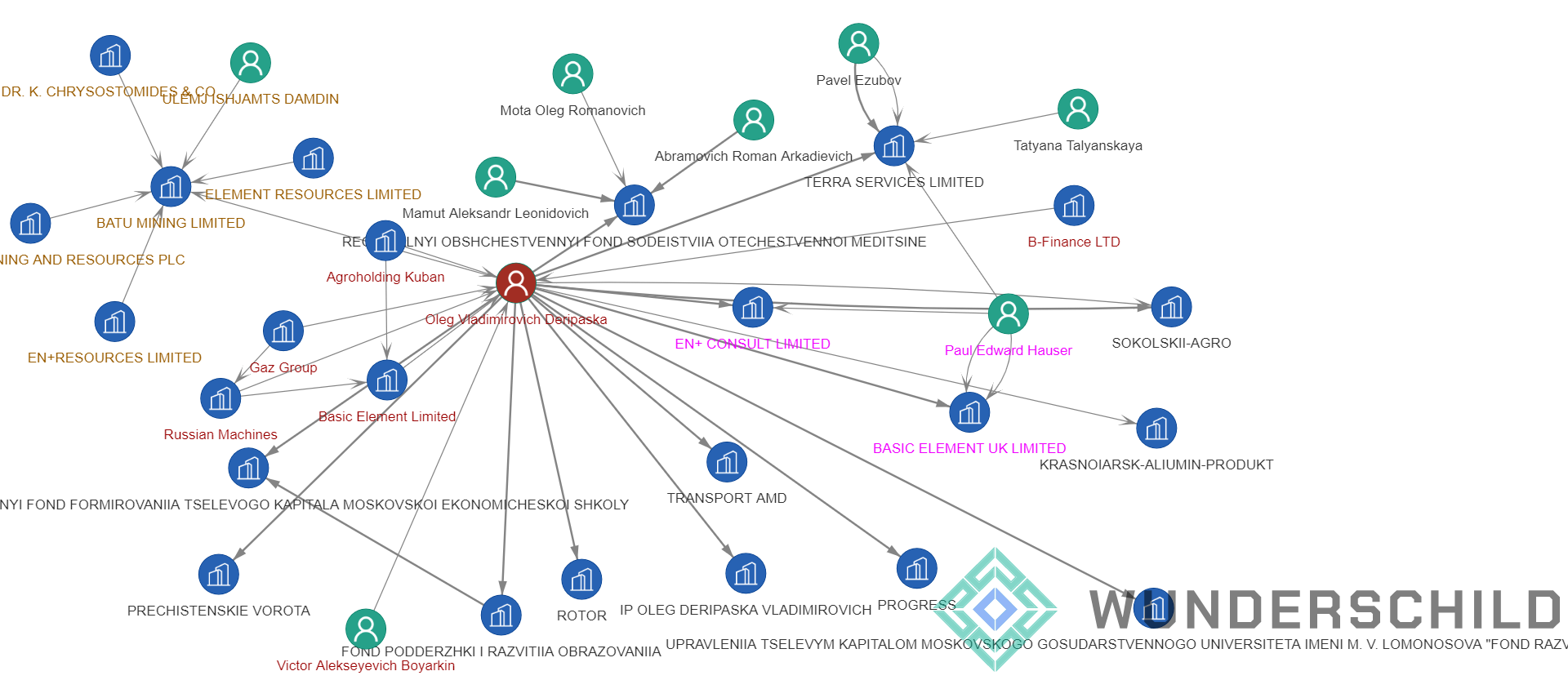

The best example of 90s-style privatisation is the case of the Russian aluminium producer RUSAL. Behind RUSAL is the iconic figure of Oleg Deripaska. In the early years of the Yeltsin era, Deripaska was an eminent student at the Moscow State University in theoretical physics. After university, Deripaska started as a metal trader in the early 1990s when a ton of aluminium was bought for USD 400 and sold for USD 1,200. Deripaska took over the various aluminium plants during the roaring 1990s in the so-called “aluminium wars”. The aluminium wars involved various criminal organisations that fought to control production capacities based in the cities along the trans-Siberian railroad (Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Bratsk) and close to cheap hydropower plants. In this war, Deripaska was backed by a controversial Russian-Israeli businessman Michael Cherney.

The Putin era

When Vladimir Putin started his reign in the early 2000s, many oligarchs of the Yeltsin era failed into disgrace. Instead, a new breed of sharper and brighter oligarchs rose to power. Oleg Deripaska is one of those controversial businessmen who gained momentum in the Putin era. Putin aimed to modernise Russia’s economy and attract foreign investors. His oligarchs were the perfect ambassadors for achieving this goal.

For instance, RUSAL went public in January 2010 after being listed in Hong Kong and Paris, raising more than USD 2.24 billion by selling 11% of its market capitalisation. However, the IPO was clouded by the controversy surrounding its massive debt accounting for USD 15 billion and a lawsuit against its owner.

Between 2000 and 2014, oligarchs reached the peak of their power. Most Western countries have rolled out the red carpet to attract the new tycoons from the East. London, Paris and New York were competing to attract oligarchs’ money and generate new business opportunities.

After the 2016 elections

War in Donbas, Crimean referendum and Trump’s election … The 2014-2016 period represented a structural break in the relationship between the West and Putin’s oligarchs. In only a few years, the Russian tycoons became pariahs in the business circles. Friends become foes. Corporations and banks severed all direct and indirect ties with the oligarchs. Several institutions have paid a high price for continuing to deal with the oligarchs. Sanctions lists focused more on oligarchs and their connections. The twilight of the oligarchs is here, and a new dawn is coming.

“An oligarchy of private capital cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organised political society because under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information.”

Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize winner

Focus: Oleg Deripaska

With an estimated net worth of USD 5 billion, Deripaska is the founder of Russian aluminium giant Rusal, listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. He still owns a stake via his shares in its parent company En+ Group.

During the 2008 financial crisis, Deripashka's wealth shrunk suddenly, and he was close to losing everything as his primary investment Rusal suffered a USD 6 billion loss in less than one year. Furthermore, Deripaska, a close associate of Vladimir Putin, was among the first recipients of bailouts from the state-owned Development Bank for USD 4.5 billion, representing almost double the upper limit of a bailout fixed by the bank.

Deripaska had a close relationship with reputed British politicians, including Lord Mandelson, former Labour Cabinet minister, George Osborne, former chancellor of the Exchequer and Nathanael Rothschild, socialite and businessman, member of the powerful Rothschild dynasty.

After being included in the US Treasury’s sanctions list, Deripaska relinquished control in En+ Group as part of his deal with the Trump administration that removed those companies from the blacklist but kept him on it.

Focus: Credit Suisse International

The Financial Conduct Authority imposed on Credit Suisse International a financial penalty of 147 million GBP. According to the FCA notice, between 1 October 2012 and 30 March 2016, Credit Suisse failed to counter the risk of being used to facilitate financial crime. Credit Suisse arranged, promoted and provided funds for two loans to finance two infrastructure projects in the Republic of Mozambique, one relating to a coastal surveillance project and the other relating to creating a tuna fishing industry within Mozambican waters. As a result, there was a high risk of bribery and corruption associated with the loans, totalling USD 1.3 billion.

While the Swiss bank conducted due diligence on all parties involved in the deal, the risk assessment was done for each risk driver on a standalone basis and “failed to adequately consider them holistically”. Know Your Network!

Word on the street: Air Cocaine

The “Air Cocaine” case made headlines in 2013 with the arrest of four Frenchmen in Punta Cana. They were part of a drug trafficking gang between the Dominican republic and frame that used luxury private jets to transport huge amounts of cocaine.

Last week, the airline officials involved in the Air Cocaine affair were released after their appeal to the highest French court. Pierre-Marc Dreyfus, 56, and Fabrice Alcaud, 48, were initially found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison. The two men were pilots of a Falcon private jet that carried 26 suitcases containing 700 kilos of cocaine in March 2013 at the Dominican airport of Punta Cana. However, after eight years of battles in court, the French justice released the Air Cocaine pilots while the other members of the gang were awaiting their release from prison.